Interview

“Some/One” and the Korean Military

Do Ho Suh installs Some/One (2001) at the Seattle Art Museum, Washington, 2002. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories, 2003. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Do Ho Suh discusses his time in the Korean military, and how it informed his 2001 sculptural installation Some/One.

Art21: Why do you have these military supplies in your studio? What’s your interest in them?

Suh: I have some old army surplus stuff that I collected for a school assignment, which ended up being the first sculpture in my life. I didn’t actually use these things. I was going to, but I sort of changed my mind. Somehow the project came from collecting these materials and also from my interaction with the army-and-navy-surplus store owner, who happened to be an old Korean guy in Cranston, Rhode Island.

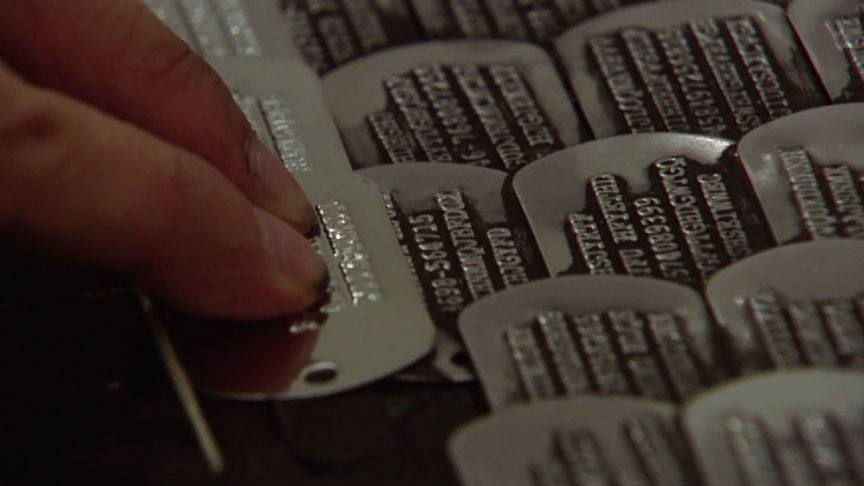

I explained to him that I was doing a project at school, and he gave me a lot of stuff for free. And he had many dog tags. At the army surplus, they make dog tags for you. And sometimes they make a mistake and spell wrong, and so they have these rejects. And also, he helped me to get the blank dog tags and gave me a really good deal. Not only that, he allowed me to use this special typewriter for the dog tags. And it was spring break, so I went there every day, I think, for almost two weeks and typed dog tags. And I had around thirty thousand dog tags there. And we had a conversation, you know; we talked about things going on, back in Korea.

But it all started with an assignment for this sculpture class that I accidentally took. I was a painting major at RISD (Rhode Island School of Design), and at RISD, you have to take at least one non-major elective studio course. And I wanted to take a glassblowing class, but it was already filled. So, this sculpture course was the only course that was open. And it was called “The Figure In Contemporary Art.” It changed my life because it was just such an important experience, and after that class, I slowly abandoned my painting and then became a sculptor. The assignment was using the form of clothing to address this issue of identity. And that was only one semester after I came here from Korea. That was also right after the L.A. riots, and I think there were some issues related to the Korean-American communities in L.A. during the riots. That was what really allowed me to think about my identity as a Korean in the United States, through that project. I think somehow my experience in the military in Korea was also something that I wanted to address through the project. So, that’s why I got into the whole military stuff.

Do Ho Suh installs Some/One (2001) at the Seattle Art Museum, Washington, 2002. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories, 2003. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Art21: Unlike the United States, in Korea, young males are required to do military service. What was that like for you?

Suh: Yes, every male has to go. It’s mandatory. I was in the army for almost two years. It’s probably a different experience than here, because from the moment that you’re born, you know that you’re going to be in the military. Everybody has to go. And so, that’s a great deal of the Korean man’s identity. And usually everyone goes to the military right after they graduate from high school. It’s a good initiation to the real world because the whole Korean society, the whole system, is actually based on this militaristic, very hierarchical structure. So, you learn a lot of things from the military before you have a real job.

I was a little bit of a different case. I was probably one of the oldest soldiers in the entire division because I went to graduate school and then went to military. So, I was, like, six or seven years older than most of the soldiers. I was the same age as a captain, so it was quite an experience. I mean, physically it was very difficult. But at the same time I was just old enough to take everything too seriously, I guess.

I was really good at many things. I was a sharpshooter. And I had a black belt before the military, so that was easy. And I could run really fast and that was very helpful. But because of my age, I think it took me longer to recuperate from the hard training. And the way they treat you . . . Basically, they train you as some kind of—you know, I don’t know if this is something that I should say or not—but after several weeks of boot camp, there were, like, two days of vacation. And I felt that I cannot be killed—like, anything—so, like, if a car hits you . . . I felt like I could survive that. That’s actually a good way of putting it. The whole program was basically pushing your psychological and physical limits to extremes, so actually you can kill someone.

And, you know, that whole experience was very difficult to swallow. It’s a process of dehumanization. And you got a lot of punishment. Now it sounds really hilarious, but during that time, it was like, “This is crazy!” I have some great stories, but I think they’re irrelevant. Like, the younger kids didn’t really care, you know. And for me, everything was something to think about. So, I think that was the difference, of being a little bit older than other guys.

I wanted to come to the U.S. even before I joined the army. But I think, in the army, I experienced what it means to be dehumanized. So, that was tough. I was challenged in many different ways, physically, but also it wasn’t like the army that I always imagined. It was a very difficult time, but at the same time, I’m glad that I did it. Every man talks about it, their own experience in the military. You know, like, when you have a drink with someone, and it’s just unbelievable. They’re unbelievable stories. And also they were funny times. Great times, too, unreal mostly.

Art21: Why does this American military equipment bring up these memories for you?

Suh: Basically we used almost the same equipments as Americans. The whole thing is based on the U.S. military system. I think also that, probably, most Korean men also have this interest—I don’t know if it’s the right word—but some kind of fetishism about this stuff. In Korea, it’s illegal to buy or have military stuff. So, when I saw these things, I wanted to get it. But after that piece was done, I never actually opened this box. It was sealed until now. And I just really didn’t need to look at it.

Do Ho Suh installs Some/One (2001) at the Seattle Art Museum, Washington, 2002. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories, 2003. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Art21: What did your first sculpture, Metal Jacket, look like—the one you made for your sculpture class?

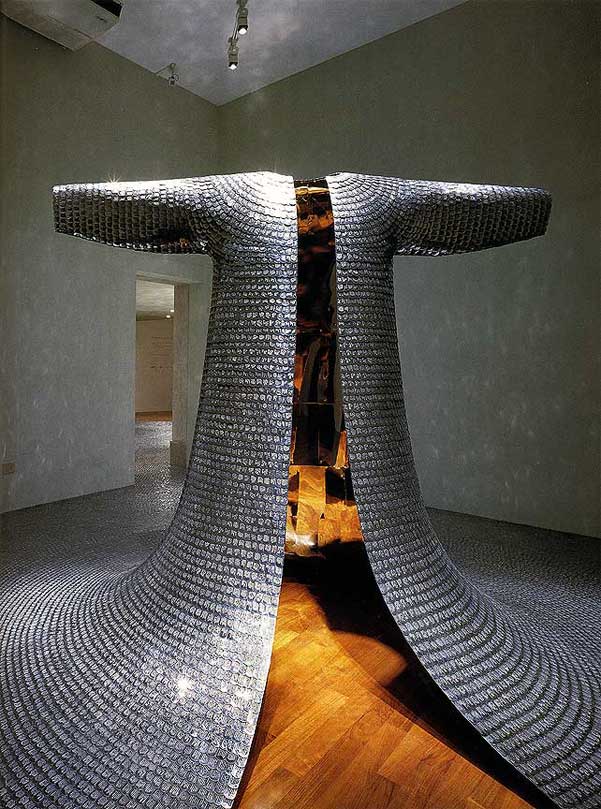

Suh: It looks like a kind of ancient Oriental armor. The first sculpture was covered with three thousand military dog tags. From a distance, the dog tags look like fish scales. The shape of that jacket was not something that I invented. I used the U.S. military jacket liner and just put the dog tags on top of it. So, I used all contemporary materials, but they ended up looking like ancient ones.

Art21: Maybe this is a silly question, but do you think your experience in the military influenced your decision to become a sculptor?

Suh: I didn’t even want to be a sculptor at all, that’s one thing for sure. And I didn’t want to make something about the military at all, either. But gradually, it came very naturally. For me, again, this experience in the military was not something special, because everyone had to go through and has to go through that process in Korea. So, if you talk to someone who went to military, they all have similar stories. That made me a little bit more comfortable to use this military experience. Maybe it’s something special here in the States. But if I show Some/One in Korea, then I think it will get a different response because it was part of their everyday life.

Art21: Where did the dog tags come from, and what do they mean to you?

Suh: I became interested in the idea behind the military dog tag. It’s a form of identification, and it’s made out of stainless steel. So, it’s a permanent material; it will not rust. And each soldier has to carry two dog tags. And when a soldier is killed in battle, one dog tag has to remain on the dead body, and one is taken away by a surviving soldier in order to report the death of that soldier, in order to secure the identity of that soldier. (I don’t think it’s actually a practical thing to do, but you put these dog tags in your mouth—so, basically, between your upper and lower teeth—and you just kick your jaw, and then that will go between your teeth. This is what I was told to do in Korea and in the military.)

Do Ho Suh. Some/One, detail, 2001. Installation view at Korean Pavilion, Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York.

Art21: What was the title of that first sculpture?

Suh: The title of that work is Metal Jacket. I was almost going to use Full Metal Jacket, but I think that was too much.

Art21: Are the dog tags typed in English or in Korean?

Suh: Oh, it’s in English. Yes, English and numbers. It’s totally nonsense, just a series of letters and numbers.

Art21: Can you talk a little about Some/One?

Suh: Well, Some/One evolved from that first sculpture, Metal Jacket. The old work never goes away. It stays there; you just don’t notice it. But I think, in the back of my mind, I constantly thought about it. I had a dream one day, after I finished Metal Jacket, when I knew that I wanted to turn this piece into some kind of larger installation, but I didn’t have the money, space, or the chance to do it. But I think, at a subconscious level, I had been thinking about it for a long time.

And the dream was quite vivid. It was night, and I was outside of this kind of football stadium, and I was approaching this stadium from the distance. And I saw this light in the stadium, and so I thought there’s some kind of activity going on. And as I approached the stadium in order to enter the stadium, I started to hear these clicking sounds, like the sound when the metal pieces touch together. It was like there were thousands of crickets in the stadium. And then I entered the stadium in the way that the football players enter the stadium. I walked slowly and went into the stadium on the ground level, and then I see this reflecting surface in the dream. And I realized I was stepping on these metal pieces that were the military dog tags. And it was slightly vibrating; the dog tags were touching each other, and the sound was from that. And from afar, I saw the central figure in the center of the stadium. I slowly proceeded to the center, and then I realized it was all one piece that gradually rose up and formed this one figure. And it tried to go out the stadium but couldn’t go out because the train was just too big—you know, it was just too big to pull all the dog tags.

So, that was the dream and the image that I got. After that, I made a small drawing. The small drawing was about this vast field of military dog tags on the ground and then a small figure in the center. That was the image I got, and I just waited. I waited for the right time to come. I mean, obviously, I could not create the piece that I dreamed of; it’s impossible. But it was a kind of image and a kind of hope. That was the impact that I wanted to somehow convey through that piece.

Do Ho Suh. Some/One, detail, 2001. Installation view at the Seattle Art Museum, Washington, 2002. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories, 2003. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Art21: When the viewer approaches the piece, it’s a similar experience to your dream because the figure of Some/One is hollow, and inside are all these mirrors. It comes as quite a surprise.

Suh: Every time I install Some/One, you always face the back of the piece, first. That’s how I orient my piece. And that means you don’t see the interior of the piece when you enter the room. You have to go through the steps, and walk on the piece, and then walk around the piece. And then, finally, you face the front of the piece, and then you are able to see the inside of the piece. And that moment is very important, I think—not only experiencing the piece physically, by stepping on the dog tags, but also when you see the reflection of yourself inside of the piece. Then, you truly become a part of the piece.

I wanted the viewer to have an experience with these little dog tags, these thousands of dog tags. It symbolizes each individual’s identity: these many dog tags create this one, larger-than-life figure. It’s ambiguous whether you’re a part of it or not, whether you are the owner of this robe when you see your own image over there. So, that’s why I had the mirror inside. And also, it’s an ideal situation because it gives the inside a particular lighting. It’s hard to create that kind of situation, but because of the illusion and the reflection, you feel like there is another dimension inside. It’s just really hard to see the depth and where the surface stops. It’s really hard to see that, and it becomes like another dimension.

Do Ho Suh. Some/One, detail, 2001. Installation view at Korean Pavilion, Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York.

Art21: Do you intend for the work to be read in a particular way?

Suh: I knew that if I extended the train or tail of the Metal Jacket piece, that it would look like an emperor’s robe. So, I went with that. But it could be read as so many different things. Somebody told me it reminded [him] of Christ or that statue in Rio de Janeiro. And a lot of Koreans think that it looks like the armor of this very famous general in the fifteenth century, who protected Korea from Japanese invasion; and we have a statue of him in the center of Seoul. Also, this general invented a battleship that looks like a turtle. And the turtle has this exoskeleton that looks like fish scales. And the way they arranged the metal on the ship was exactly the same way I did it in the Some/One piece. So, not only General Lee but also his ship and everything else somehow all come together in this one piece. I allow people to make multiple associations to the work; I really like it, when that happens. I don’t know whether it’s simply coincidence or not, but I think I carefully managed to keep the work open, so it could be read in different ways.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.